William Bell features in Chapter II of A H Savory’s Grain and Chaff from an English Manor. Arthur Savory obviously had a great respect for William Bell as he is the first employee we are introduced to and the character sketch runs to several pages; he is also the only employee who is given his full name in the book:

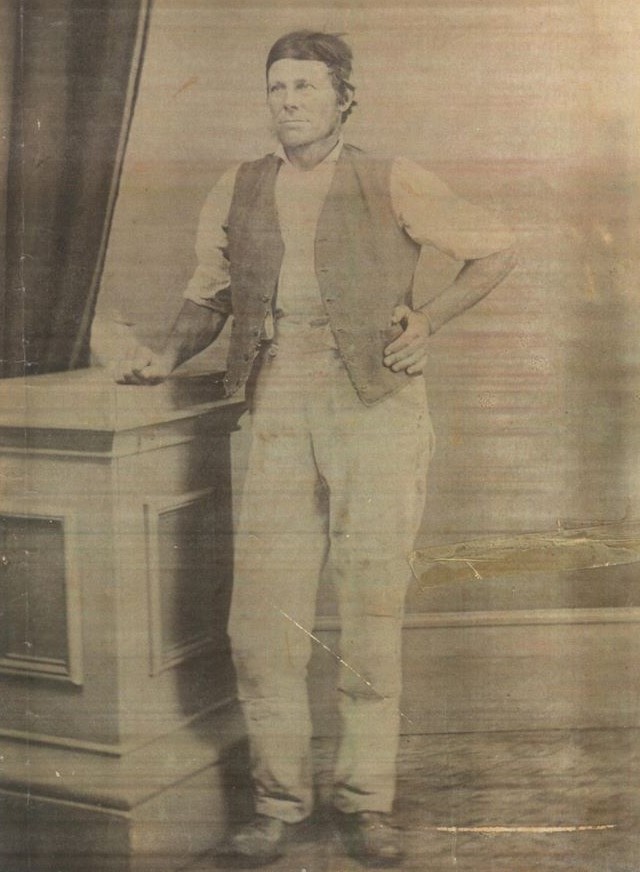

I soon recognised that I had a splendid staff of workers, and, under advice from the late tenant, I selected one to be foreman or bailiff. Blue-eyed, dark-haired, tall, lean, and muscular, he was the picture of energy, in the prime of life. Straightforward, unselfish, a natural leader of men, courageous and untiring, he immediately became devoted to me, and remained my right hand, my dear friend, and adviser in the practical working of the farm throughout the twenty years that followed. Like many of the agricultural labourers, his remote ancestors belonged to a class higher in the social scale, and there were traditions of a property in the county and a family vault in Pershore Abbey Church. However this might be, William Bell was one of Nature’s gentlemen, and it was apparent in a variety of ways in his daily life.

Shortly before my coming to Aldington he had received a legacy of £150, which, without any legal necessity or outside suggestion, he had in fairness, as he considered it, divided equally between his brother [Edwin Bell, 1841-1897], his sister [Hannah Hopkins, 1847-?] and himself - £50 each – and his share was on deposit at a bank. Seeing that I was young – I was then twenty-two – and imagining that some additional capital would be useful after all my outlay in stocking the farm and furnishing the house, he, greatly to my surprise and delight, offered in a little speech of much delicacy to lend me his £50. I was immensely touched at such a practical mark of sympathy and confidence, but was able to assure him gratefully that, for the present at any rate, I could manage without it. On another occasion, after a bad season, he voluntarily asked me to reduce his wages, to which of course I did not see my way to agree.

Bell was always ready with a smart reply to anyone inclined to rally him, or whom he thought inclined to do so; but his method was inoffensive, though from most men it would have appeared impertinent. In the very earliest days of my occupation the weather was so dry for the time of year – October and November – that fallowing operations, generally only possible in summer, could be successfully carried on, a very unusual circumstance on such wet and heavy land. Meeting the Vicar [Reverend Thomas Hunt], a genial soul with a pleasant word for everyone, the latter remarked that it was “rare weather for the new farmers”. Bell, highly sensitive, fancied he scented a quizzing reference to himself and to me and knowing that the Vicar’s own land – he was then farming the glebe with a somewhat unskilful bailiff – was getting out of hand, replied: “Yes, sir, and not so bad for some of the old’uns.” Bell happened to pass one day when I was talking to the Vicar at my gate. “Hullo, Bell,” said he, “hard at work as usual; nothing like hard work, is there?” “No, sir,” said Bell, “I suppose that’s why you chose the one-day-a-week job!”

Bell’s favourite saying was, “If a job has to be done you may as well do it first as last,” and it was so strongly impressed upon me by his example that I think I have been under its influence, more or less, all my life. He was certain to be to the fore in any emergency when promptitude, courage and resource were called for; he it was who dashed into the pool below the mill and rescued a child and when I asked if he had no sense of the danger simply said that he never thought about it. It was Bell who tackled a savage bull which, by a mistaken order, was loose in the yard and which, in the exuberance of unwonted liberty, had smashed up two cow-cribs and was beginning the destruction of a pair of new bar doors, left open, and offering temptation for further activity. The bull, secured under Bell’s leadership and manacled with a cart-rope, was induced to return to its home in peace. When felling a tall poplar overhanging the mill-pond, it was necessary to secure the tree with a rope fixed high up the trunk and with a stout stake drive into the meadow, to prevent the tree falling into the pond. Bell was the volunteer who climbed the tree with one end of the rope tied round his body and fixed it in position. He was always ready to undertake any specially difficult, dirty or hazardous duty and in giving orders it was never, “Go and do it,” but “Come on, let’s do it.” An example of this sort was not lost upon the men; they could never say they were set to work that nobody else would do and their willing service acknowledged his tact.

One day a widow tenant asked me to read the will at the funeral of an old woman lying dead at the cottage next her own. I consented and reached the cottage at the appointed time. It was the custom among the villagers, when there was a will, to read it before, not after, the ceremony as, I believe, is the usual course. I found the coffin in the living-room and the funeral party assembled and the will, on a sheet of notepaper, signed and witnessed in legal form, was put into my hands. Looking it through, I could see that there would be trouble, as all the money and effects were left to one person to the exclusion of the other members of the family, all of whom were present. It was quite simply expressed and, after reading it slowly, I inquired if they all understood its provisions. “Oh yes,” they understood it, “well enough.” I could see that the tone of the reply suggested some kind of reservation; I asked if I could do anything more for them. The reply was “No,” with their grateful thanks for my attendance; so, not being expected to accompany the funeral, I retired. I was no sooner gone than the trouble I had anticipated began and the disappointed relatives expressed their disapproval of the terms of the will, some going so far as to decline to remain for the ceremony. Bell was not among the guests or the bearers but, hearing raised voices at the cottage and guessing the cause, he boldly went to the spot and, in a few moments had, with the approval of the sole legatee, arranged an equal division of the money and goods; whereupon the whole party proceeding in procession to the church. I think no one else in the village could so easily have persuaded the favoured individual to forgo the legal claim; but Bell was no ordinary man and his simple sincerity of purpose was so apparent that his influence was not to be resisted.

Bell’s cheerfulness and his habit of making light of difficulties were very contagious. I had early recognised the seriousness of the problem presented by the foul condition of the land but, as we gradually began to reduce it to better order, I remarked that the prospect was not so alarming after all. His reply was that when once the land was clean and in regular cropping, “a man might farm it with all the playsure in life”.

Though no “scholard”, his wonderful memory stood him in good stead and was most valuable to me. He came in for a talk every evening to report the events of the day and arrange the work for the morrow. After a long day spent with one of the carters delivering such things as faggots of wood, he would recall the names of the recipients and the exact quantities delivered at each house without the slightest effort. His only memoranda for approximate land measurements would be produced on a stick with a notch denoting each score, yards or paces. He could keep the daily labour record when I was away from home; but though I could always decipher his writing, he found it difficult to read himself. A letter was a sore trial and he often told me that he would sooner walk to “Broddy” (Broadway) and back, ten or eleven miles, than write to the veterinary surgeon there, whose services we sometimes required.

We had a simple method of disposing of small pigs; it was an understood thing that no pig was to be sold for less than a pound. I had a good breed, always in demand by the cottagers, who never failed to apply, sometimes, perhaps, before the pound size was quite reached, as it was a case of first come first served, and there was the danger that the best would be snapped up before an intending buyer could have his choice. Bell’s face was wreathed in smiles when he came in and unloaded a pocketful of sovereigns on my study table saying, when trade was brisk, “I could sell myself if I was little pigs!”

Many and anxious were the deliberations we held in the early days of my farming; the whole system of the late tenant was condemned by my theoretical and Bell’s practical knowledge but they did not invariably coincide and, after a long discussion on some particular point, he would yield, though I could see that he was not convinced, with, “Well, I allows you to know best.”

When, a few years later, I introduced hop-growing as a complete novelty on the farm, he regarded it at first as an extravagant and unprofitable hobby, akin to the hunters my predecessor kept. He “reckoned”, he said that my hop-gardens were my “hunting horse” and I heard that my neighbours quoted the old saw about “a fool and his money”. Bell was not so enlightened as to be quite proof against local superstitions; I had to consult his almanac and find out when the “moon southed” and when certain planets were in favourable conjunction, before he would undertake some quite ordinary farm operations.

He was a clever and courageous bee-master and “took” all my neighbours’ swarms as well as my own, my gardener not being “persona grata” to bees. The job is not a popular one and he would, when accompanied by the owner, always ask, “Will you hold the ladder or hive ‘em?” The invariable answer was, “Hold the ladder.” He firmly believed in the necessity of telling the bees in cases where the owner had died, the superstition being that unless the hive was tapped after dark, when all were at home and a set form of announcement repeated, the bees would desert their quarters.

Bell was an excellent brewer and, with good malt and some of our own hops could produce a nice light bitter beer at a very moderate cost. In years when cider was scarce we supplemented the men’s short allowance with beer, 4 bushels of malt to 100 gallons; and for years he brewed a superior drink for the household which, consumed in much smaller quantities and requiring to be kept longer, was double the strength. His methods were not scientific and he scorned the use of a “theometer”, his rule being that the hot water was cool enough for the addition of the malt when the steam was sufficiently gone off to allow him “to see his face” on the surface.

Owing to his having lived so long in such a quiet place, and the limited outlook which his surroundings had so far afforded, Bell was somewhat wanting in the sense of proportion, and when I had a field of 10 acres planted with potatoes, he told me quite seriously that he doubted if the crop could ever be sold, as he did think there were enough people in the country to eat them!

Soon after the reopening of the church I overtook Bell as we were returning from Sunday morning service. It was a dark day and the pulpit, having been moved from the south to the north side of the nave – farther from the windows – the clerk lighted the desk candles before the Vicar began his sermon. I asked Bell how he liked the service, referring to the new choir and music; he hesitated, not wanting, as I was the Vicar’s churchwarden, to appear critical, but being too conscientious to disguise his feeling. I could see that he was troubled and asked what was the matter. Then it came out; it was “them candles!” which he took to be part of the ritual, and he added, “But you ain’t a-goin’ to make a Papist of me!”

Bell was proof against attempted bribery and often came chuckling to me over his refusals of dishonest proposals. A man from whom I used to buy large quantities of hop-poles required some withy “bonds” for tying faggots; they are sold at a price per bundle of 100 and the applicant suggested that 120 should be placed in each bundle. Bell was to receive a recognition for his complicity in the fraud and he agreed on condition that in my next deal for hop-poles 100 should be represented by 120 in like manner. The bargain did not materialise.

I found Bell a very amusing companion in walks and excursion we took to fairs and sales for the purchase of stock. He knew the histories and peculiarities of all the farmers and country people whose land or houses we passed and his stories made the miles very short. I often helped with driving sheep and cattle home, and their persistence in taking all the wrong turning or in doubling back was surprising; but two drovers are much more efficient than one and we got to know exactly where they would need circumventing. When we visited a town I always took him to an inn or restaurant and gave him a good dinner. Visiting what was then a much-frequented dining place – Mountford’s at Worcester, near the cathedral – we sat next to a well-known honourable and reverend scholar of eccentric habits. He would read abstractedly, forgetting his food for several minutes, then suddenly would make a noisy dash for knife and fork, resuming the meal with great energy for a while, and as suddenly relinquish the implements and return to his reading and so on continuously. I noticed Bell watching with great surprise, much shocked at such unusual table manners and presently he could not forbear very gently nudging my elbow to draw my attention to the performance.

It was a popular village belief that bad luck follows if a woman was the first to enter a house on Christmas morning and Bell always made a point of being the first over my threshold, shouting loudly his greeting up the staircase.

Bell’s wife [Sarah Bell, née Harris, 1836-1917] survived him, living on in the same cottage in which he was born and had passed his life. She was a hard-working woman, and came over to my house once a week for some years to bake the bread, made from my own wheat ground at the village mill.

I had a very human dog, Viper, partly fox-terrier; though not very “well bred”, his manners were unexceptionable and his cleverness extraordinary. One summer afternoon Mrs Bell was greatly surprised by Viper coming to her house much distressed and trying to tell her the reason; he was not to be put off or comforted, and, seizing her skirts, he dragged her to the door and outside. She guessed at once that her two boys [Alfred Bell, 1871-1935, and Henry William Bell, 1876-1923] were in some danger, and she followed the dog. He kept running round to make sure that she was close behind, and led her down a lane, for perhaps 300 yards, to a gate leading into a 12-acre pasture. They pursued the footpath across the field, through another gate and over the bridge which spanned the brook, into a meadow beyond. There she found the children in fear of their lives from the antics of two mischievous colts which were capering round them with many snorts and much upturning of heels. It was really only play, but the boys were alarmed, and viper, who had accompanied them, had evidently concluded that they were in danger.

Before the days of the safety bicycle an excellent tricycle, called the “omnicycle” was put on the market; and the villagers were greatly excited over one I purchased, of course only for road work, expecting me to use it on my farming rounds; and Mrs Bell was heard to say, “I knows I shall laugh when I sees the master a-coming round the farm on that thing.”

Bell always spoke of her as “my ‘ooman” and, referring to the depletion of their exchequer on her returns from marketing in Evesham, often said, “I don’t care who robs my ‘ooman this side of the elm” – a notable tree about halfway between the town and the village – knowing that she would have very little change left.

In a later chapter, Savory talks about a wedding feast on the occasion of his bailiff’s daughter. This was Annie Bell, William Bell’s only daughter, who married William Marsh in April 1885 at Wickhamford (Badsey Church at the time was closed for refurbishment). Arthur Savory was one of the witnesses who signed the marriage register:

I was invited to the wedding feast of my bailiff’s daughter, and being, I suppose, regarded as the principal guest, was, according to custom, requested to carve the excellent leg of mutton which formed the pièce de resistance.

William Bell (1837-1894) was born at Aldington in 1837, the eldest of three children of Henry Bell, an agricultural labourer, and his wife, Fanny (née Tael). His father died suddenly in 1853; his mother remarried in 1863 to Joseph Brooks Morris.

William married Sarah Harris at Badsey on 17th September 1860. They had three sons and one daughter, their first son dying at just a few days: Henry (1861-1861), Annie (1866-1945), Alfred (1871-1935) and Henry William (1876-1923). In 1861, William was working as an agricultural labourer and they lived in the house now known as Corner Cottage, Main Street, Aldington. William lived there for the rest of his life; the cottage remained in the Bell family until the death of William’s great-grandson, Geoff Bell, in 2005..

William worked at Aldington Manor Farm, firstly under Thomas Blyth, then under Arthur Savory, who appointed him farm bailiff soon after his arrival in Aldington in 1873.

William Bell died at Aldington in April 1894, aged 57. His widow, Sarah, survived him by over 23 years, dying at Aldington in 1917, aged 81.