In telling the story of Annie Bell and William Marsh and their emigration to Ohio, it became apparent that they, and the other emigrants from the parishes of Badsey, Aldington and Wickhamford, were part of a much bigger migration to America. This article sets their story in the wider historical context, both locally, nationally and internationally. Let us begin by looking at what was going on locally.

The Local Scene

The Aldington Enclosure Map of 1808 shows quite clearly that the local economy was based on arable farming, with the village surrounded by large fields owned by local landowners such as Thomas Bird and George Day, the tenant of Aldington Manor at this time. By the time of the first Ordnance Survey map of the village in 1883, the year William Marsh first emigrated to Ohio, land use had changed dramatically, with much smaller fields and large areas given over to orchards. Indeed the Kelly’s Directory of 1888 states “The land is fertile, chiefly arable. This hamlet contains about 632 acres; much land is devoted to garden purposes and hops are grown here; rateable value, £2,244; the population in 1881 was 135.” The list of people includes, as well as the local landowners, 19 businesses, of which 14 were market gardeners. Fruit growing and hops were part of the innovations introduced by Arthur Savory, the tenant of Aldington Manor, and the advent of market gardening as a way of generating income for the landowners is well covered in depth elsewhere.

What had caused these changes?

The situation is well summed up by a quote from Chapter 4 of Grain and Chaff from an English Manor, attributed to Jim, the head carter of the estate:

“Jim had sufficient foresight to view with alarm the gradual dispersion of most of the oldest and best farmers in the neighbourhood, and the conversion to grass of the arable land, owing to the unfair and dangerous competition of American wheat. When we discussed the subject and foretold the straits to which the country would be reduced in the event of war with a great European Power, he concluded these forebodings with the habitual remark, "Well, what I says is, them as lives longest will see the most." A truism, no doubt, but, as time has proved, by no means an incorrect view.”

The decline in the fortunes of agriculture began with the repeal of the Corn Laws in January 1846. The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and grain enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word 'corn' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were designed to keep grain prices high to favour domestic producers.. The Corn Laws blocked the import of cheap grain, initially by simply forbidding importation below a set price, and later by imposing steep import duties, making it too expensive to import grain from abroad, even when food supplies were short. Once they were gone, imports of corn from America, fuelled by the opening up of the American prairies to cultivation in the 1870s, drove down British corn and meat prices. At the same time, mechanisation of agriculture was increasing worldwide, and the advent of steamships led to faster, cheaper Atlantic crossings. This gave rise to the Great Agricultural Depression, which is usually dated from 1873 to 1896.

At the same time as the agricultural landscape was changing, so was the nature of democracy in Britain as a result of the Representation of the Peoples Act 1884. This gave all men paying an annual rent of £10 and all those holding land valued at £10 the vote and gave agricultural workers control of their own destiny for the first time, in line with their counterparts in the towns and cities, especially in the Vale of Evesham, where men had taken advantage of the small parcels of land that they could rent in order to grow market garden crops. This was a double edged sword for many, however, as with falling prices, economic necessity led to mass emigration, particularly of young, single men.

As well as the national and local economic conditions, there were many other local influences on William Marsh that must have affected his decision to emigrate to Ohio for the first time in 1883. The local newspapers were full of advertisements from both shipping lines and their agents for cheap passages to America, with frequent sailings, at least weekly from as little as £4. On top of this steerage passengers had to provide their own beds, bedding and eating utensils. William would probably have bought his ticket from one of the agents in Worcester.

In addition, many gentlemen of means travelled extensively in North America and published guides and books on their return. They also wrote glowing letters to the newspapers on their return.

One such person was W. Henry Barneby of Bredenbury Court near Worcester, the Conservative MP for the area. He was also an author of some note, and in 1884 his new book “Life and Labour in the Far Far West” was published for the price of 16s by Cassell & Co. Ltd. of London. This was described as being very entertaining, and came from his tour of the far west during the Spring and Summer of 1883, where he passed through some of the finest scenery in North America. He had lots of opportunities to observe the condition of Agriculture, especially in the Dominion of Canada and British Columbia, and of considering the suitability of the country as a “field for emigration” and for the “investment of capital”.

Sir Richard Temple, the MP for Evesham also gave a lecture on “America” at the YMCA in Copenhagen Street, Worcester on 2 January 1883, three months before William emigrated at the first time, in which he spoke very highly of the reception given to English emigrants, and this was reported in the Worcestershire Chronicle four days later. William would almost certainly have read this article.

Sir Richard Temple became MP for Evesham in 1885 after a distinguished career in the Indian Civil Service. He visited Arthur Savory, Annie Bell’s employer at Aldington Manor in 1885 to canvass him and the villagers of Badsey. This was reported in Savory’s book, Grain and Chaff from an English Manor. No doubt the subject of emigration would have come up during this visit to the locality.

How did William travel to America?

There were two main routes from Europe across the Atlantic, either via Rotterdam or Liverpool. By the 1880s the rail network in Britain was well – established, so it would have been easy to get to the ports. When William first emigrated in 1883, he travelled via the first route. When he and Annie returned after their marriage in 1885, it was via Liverpool. Let us consider both routes in a little more detail.

To get to Rotterdam, William could have travelled one of two ways. He could either have travelled to Hull via Birmingham and Leeds, arriving at the new Paragon Railway Station built in 1871 for the transfer of foreign migrants to prevent diseases such as cholera which were prevalent in Britain at that time. From Hull there were numerous services crossing the North Sea to Holland and Germany, as well as a steam packet service every Wednesday from Humber Dock. Alternatively he could have caught the train from Evesham to London, then on to Harwich, where the Great Eastern Railway Company had created a new port at Parkeston Quay in 1883 to service passenger trade with the Netherlands and Germany. These are the same two routes that are used today.

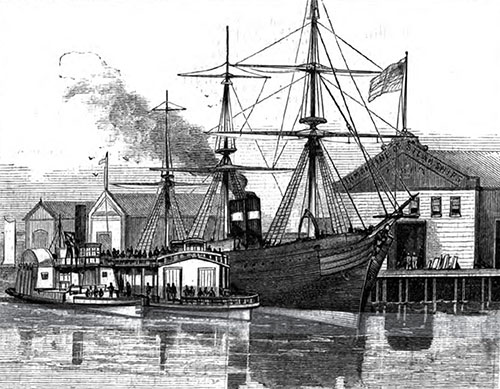

Once in Rotterdam, William transferred to the S.S Maas, a 1705 ton steamship of the Holland – America Line for the journey to New York. When she was built she had accommodation for eight first – class passengers and 288 third – class passengers, but the ship’s manifest when William landed in Castle Island on 23 April 1883 states quite clearly that there were 4 first – class passengers and 356 steerage passengers, quite a difference in numbers. This may, of course, be due to internal modifications of the vessel in the intervening years.

The ship’s manifest is a document listing the cargo, passengers and crew of a ship for the use of customs and immigration officials, and as such is a legal document signed by the ship’s master. As such it is a valuable source of information about the passengers on board. The way the information is broken down is in line with the United States Passenger Act 1882 which gave protection to passengers against overcrowding, made it obligatory to give them proper and sufficient food, air and space, and in many respects promoted their comfort and safety. It specified that there should be 100 – 120 cubic feet of space per adult. Two children between the ages of 1 and 8 counted as 1 adult, and children under 1 were not included.

The manifest for the Maas tells us a lot about the passengers on board, in particular their age, marital status and occupation:

- Passengers – 360 in total

- 4 First Class passengers, 356 Steerage

- 312 passengers aged 8 and over, 27 children aged between 1 and 8, 13 babies under 1

These comprised:

- 145 Dutch citizens

- 125 German citizens

- 36 Italian citizens

- 23 Swedish citizens

- 14 English citizens

- 3 U.S citizens

- 2 Swiss citizens

- 2 Hungarian citizens

- 1 Danish citizen

As you might expect from a vessel leaving from Rotterdam, the majority of passengers were from mainland Europe, followed by those from Scandinavia and a mere 14 English people. The majority of these were skilled tradesmen and farmers headed for the expanding economy of the mid-west.

Two years later, William Marsh returned to Aldington to marry his sweetheart Annie Bell. When the happy couple travelled back to America, accompanied by William’s sisters Annie and Alice, the party left from Liverpool on the S.S City of Richmond, a much larger ship at 4,607 tons. The Inman Line, with which they travelled, was one of the three largest British passenger shipping companies of the 19th century, and the fastest. An advertising card of the time stated:

INMAN LINE

WEEKLY BETWEEN

LIVERPOOL AND NEW YORK

THE STEAMERS OF THIS LINE

Are all amongst the largest, fastest, and most comfortable Ocean Passenger Steamers in the world. They are built with especial regard to strength, and fitted with watertight and fireproof compartments. They have long been admired for their beautiful model, great power, and excellent sea-going qualities; and have the highest reputation for speed, comfort, and regularity, their passages being amongst the shortest on record. The CABIN accommodation is of the highest order, every consideration being paid to the care and comfort of Passengers. The Saloons are large, fitted with revolving arm chairs, luxuriously furnished, especially well lighted and ventilated, and take up the whole width of the vessel amidships. The principal Staterooms are amidships, where least noise and motion is felt, and all are particularly light and airy, are fitted with electric bells, have water laid on, and every requisite to add to the comfort of an ocean passage. Ladies' sitting and retiring rooms, gentlemen's smoking room, pianos, libraries, bathrooms, barber's shop, &c., provided. Special attention has been paid to the sanitary arrangements. The cuisine has always been a speciality of this Line. STEERAGE PASSENGERS will find their comfort and convenience carefully studied in every respect. They are carried upon the same deck as the cabin passengers, the sleeping rooms being enclosed, containing a limited number in each, are well lighted, warmed, and thoroughly ventilated throughout. Ample space is provided for partaking of meals and promenading. The bill of fare includes all abundant supply of cooked provisions, served out by the Company's stewards

Like that of the Maas, the manifest for the City of Richmond details the name, age, marital status, occupation, place of birth, class of travel and amount of luggage carried. The breakdown of passengers is interesting in comparison with that of the Maas. There were 1324 passengers in total – 1208 in steerage, 69 in Intermediate accommodation and 48 in cabins. The breakdown by nationality was as follows:

Steerage

- 176 English

- 10 Welsh

- 3 Scots

- 666 Irish

- 1 French

- 6 American

- 1 Swiss

- 287 Swedish

- 2 Norwegian

- 23 German

- 13 Danish

- 5 Austrian

Intermediate

- 68 English

- 1 Canadian

Cabin

- 23 English

- 24 American

- 1 German

The Scandinavian, European and British emigrants were heading for the farming areas of the mid-west, the Irish for the industrial areas and railroad building. As ever, Irish navvies were in great demand. The predominance of Scandinavians making the crossing from Liverpool was due to the wide availability of combined ticket packages from agents in Norway, which meant that once they boarded the ship from Norway to Hull, they were escorted from one stage to the next; from Hull to Liverpool by train, then on to the ship at Liverpool. Once in New York they were processed through Castle Island and then onwards to their final destination by train. The large number of Irish passengers was due to the ship calling at Queenstown (now known as Cobh) in County Cork.

The majority of emigrants travelled in steerage, also known as ‘tween decks’ the worst and most crowded accommodation on board. The City of Richmond was typical of the large steamers of this time. Single men and women and families were segregated, with men at one end of the vessel, women at the other and families in the middle. According to “Part 1: General Directions” in the Handbook for Immigrants to the United States, published in 1871,each adult was allocated 100 – 120 cubic feet of space, with 10 cubic feet per passenger for luggage. The fare for an Inman Line vessel in 1871 was £8 7s from Scandinavia, £7 7s from Europe and £6 6s from Liverpool. Children under 12 paid half fare, and infants under 1 18s. The Handbook states:

“Steerage passengers are furnished, on steamers of all of the above lines, with an abundance of food, of good quality, properly cooked, and served by the companies' stewards three times a day.”

In fact this comprised fresh bread, tea or coffee and gruel for breakfast and supper, beef or pork, soup, fish and potatoes for dinner. In addition passengers had to provide their own mattress, bedding, eating utensils and water can, all of which were available in Liverpool for 15 shillings.

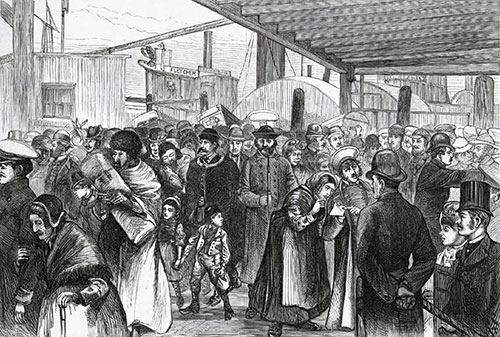

Conditions were crowded, noisy and smelly. By the 1880s, vessels had to have sanitation, access to fresh air and medical facilities on board, but the journey was still something to be endured rather than enjoyed. The sight of the Statue of Liberty on the horizon must have been very welcome to the travellers.

William and Annie, plus Alice and Annie arrived at Castle Garden, New York on 16 May 1885 after a 10 day voyage.

Castle Garden, originally known as Castle Clinton, was a circular fort built on an artificial island some 200 feet off the Battery in lower Manhattan. It was connected to the Battery by a bridge. It was the immigrant depot from 1855 – 1892 when it was succeeded by Ellis Island. Ellis Island received $75,000 government funding on 11 April 1890 and opened for business on I January 1892, 21 months later.

The whole process was a fairly slick operation. Once the City of Richmond had tied up at Castle Island, emigrants were transferred to a barge taking them to the mainland. Once there, their paperwork was examined, medical inspections undertaken and then they were taken to the railroad ticket office for transfer to the rail network for the final leg of their journey.

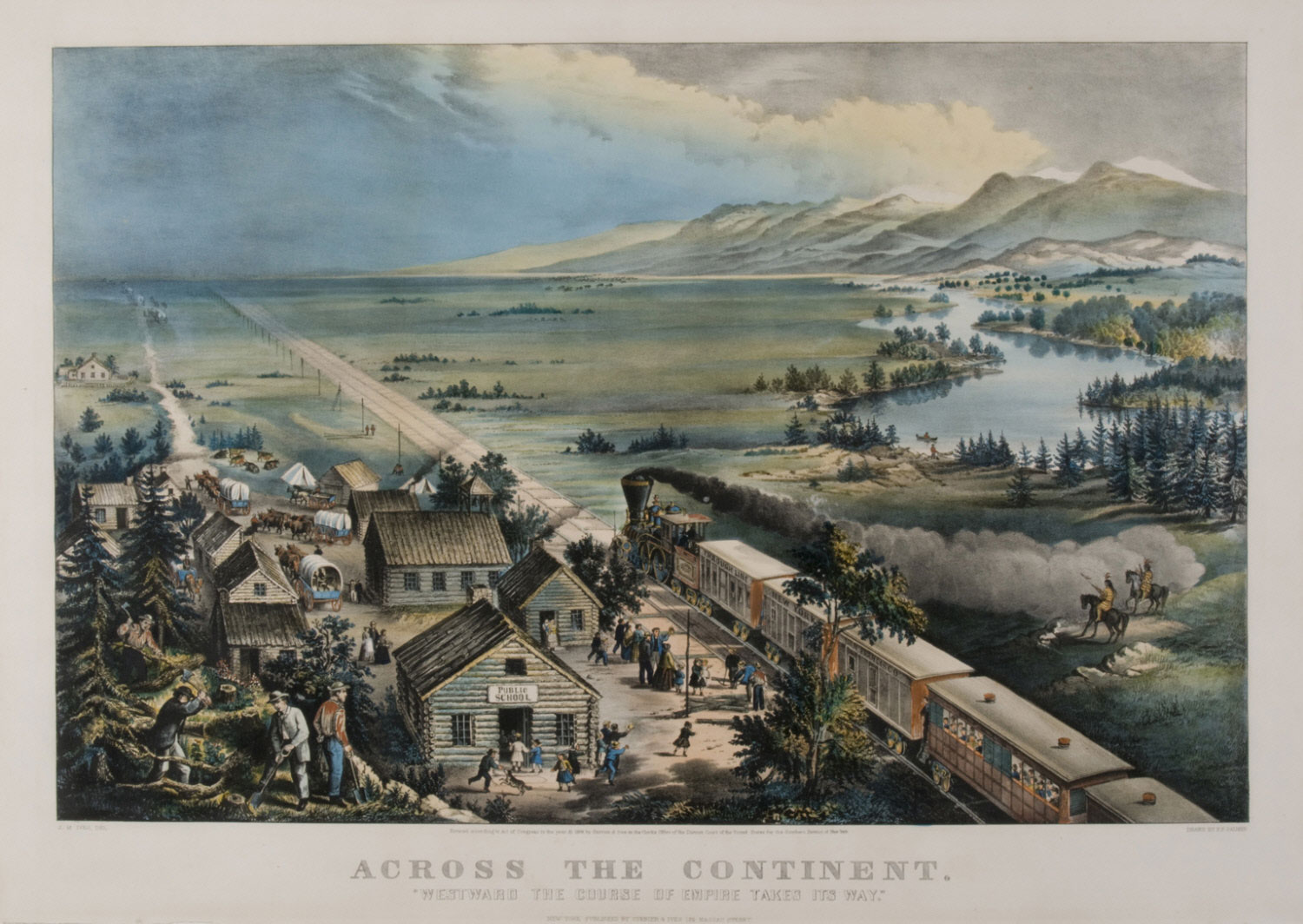

Although the earliest emigrants to Ohio would have travelled by the Erie Canal, the first rail route had been opened on 24 January 1853 by the New York Central Railroad. By 1885 there were three more services operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Erie Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The journey to Ohio would have taken 1 – 2 days and have cost somewhere in the order of £3.

What was so attractive about Ohio?

After the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the Government began to expand from the original thirteen British colonies in New England, spreading westwards. According to Britannica this was spearheaded by “the federal land managers, who surveyed, numbered and mapped their territory in advance of settlement, beginning with Ohio in the 1780s, then sold or deeded it to settlers under inviting terms at a number of regional land offices.” After New England, the Midwest, including Ohio was next, and these states were admitted between 1791 and 1860. The western states (the Wild West) followed, between 1861 and 1876, and these were the ones targeted by the Homestead Act which came into force in May 1862 and gave Americans, including African – Americans, the opportunity to buy 160 – acre plots for the cost of a small filing fee. From 1890 onwards the Territories from Montana in the north to New Mexico in the south joined the U.S.A.

This timeline of development is reflected in the pattern and layout of settlements as emigrants spread west. New England villages are laid out like an English village, with buildings grouped round a church and a village green This pattern is repeated in the earliest Midwest villages such as Burton, where William and Annie finally settled Later Midwest towns are based on a grid with a central business district surrounded by peripheral residence lots .Townships came later, and comprised 6 mile by 6 mile blocks, oriented with the compass directions, with 36 one mile square sections in each township, with public roads along section lines and half section lines. Within these sections are small settlements and individual farmsteads. Later settlements to the west and south were even more isolated.

Immigration to America from Europe had been taking place since the time of the Pilgrim Fathers, and indeed one of William and Annie’s nieces, Huldah Belle Talcott married Arthur Alvin Noyes, a descendant of a 17th Century Protestant dissenter, the Reverend James Noyes, and ancestor of Lizzie Noyes, one of the founder members of the Badsey Society. This was the time of the ‘Great Migration’, when over 50,000 English immigrants, mostly poor, indentured servants, arrived in the 13 British Colonies. German immigration to America initially centred in Pennsylvania and upstate New York during the 1700's. The early German immigrants were search of religious freedom and the opportunity for trade, and it is from within this group that the Amish originated, as they were mostly farmers. The trend began to accelerate in the mid – 19th century, as news of the expansion of agriculture and the opportunity to buy land reached Europe. The first wave of settlers was from Scandinavia, Germany, Holland, Ireland and England, followed later by Italians and other southern and eastern Europeans as the economy developed as a result of improving canal and railroad networks.

In 1834 the completion of the Ohio & Erie Canal between Cleveland and Portsmouth, Ohio took place. This 308-mile-long canal was the final link in an inland waterway connecting the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River System. The Canal allowed goods to travel from Ohio down the Mississippi to the Gulf of of Mexico and from Cleveland on Lake Erie to Buffalo and from there to the east coast. A continuation of the Erie Canal, the Ohio and Erie Canal was funded, designed and constructed by New York financiers, engineers and the Irish immigrant labour gangs. This water route was a significant part of the American System, the interstate transportation infrastructure needed to establish a national economic system for the young nation.

The canal laid the foundation for Ohio’s industrial, commercial and political development. It provided an economical way to transport goods that promoted specialization, economies of scale and the growth of profitable commerce. In addition to revenue from tolls, leases of waterpower and the rental of canal land, Ohio also gained innumerable advantages. The value of land and products in the state increased and thousands of new inhabitants settled in Ohio along the canal area. The prosperity in Ohio led to the development of small towns and cities along the waterway Cities such as Cleveland, Akron and Massillon also thrived and became nationwide leaders in shipping and production of wheat, grains, iron and steel. Merchants from Buffalo increased their purchases from Cleveland's wheat market from 1,000 bushels annually to more than 250,000 within one year of the canal opening. The canal was in active operation from its completion until just before the Civil War. By 1863 competition from the railroads was intense and the canal fell into disuse. In addition in 1855 the St Marys Falls canal between Michigan and Lake Superior opened, making Cleveland Lake Erie's’ transhipment point for lumber, copper and iron ore, and rail shipments of coal and farm produce, a classic combination of industries.

By the 1870s, the economy of Ohio was still expanding, with industry being concentrated on the area around Cleveland, and a corresponding growth in agriculture to feed the growing population in Cleveland and the towns surrounding it. The map below shows the wide range of farming at the time. This attracted immigrants from all over Europe, where the economic situation was the opposite to that in America.

Before the Civil War, farming in Cuyahoga County, the area immediately surrounding Cleveland, had been mainly dairying, orchard fruits, grapes and market gardening of vegetables, strawberries and small fruits. This was very similar in character to the Vale of Evesham, and this is what would have attracted William and Annie and the other residents of Badsey who emigrated at this time. This is well documented in the article”Emigration to America” on the Badsey Society website, and is summed up well by the following quote from an article on the Case Western University website:

“Limited to the thinly populated parts of Cleveland and its environs, it was carried on almost exclusively by European immigrants and their families, as native-born Americans had no relish for the incessant spading, hoeing, and weeding required.”

This is very similar to news reports that you might read in the UK today! The article continues:

“Of particular importance was the forcing industry, the growing of vegetables under glass for the out-of-season market. In 1900 truck growers had about 21 acres in hotbeds or cold frames and 4 acres in greenhouses; the latter concentrated in the Brooklyn area.”

Conditions were perfect for Vale of Evesham market gardeners to settle down and make their mark.

After the Civil War, farming became more industrialised. There was an increase in butter and cheese making; milk began to be produced all year round due to the introduction of silage. Milk trains from Willoughby to Cleveland were introduced in 1868 to speed up deliveries to the city, and there was an expansion of vegetable growing, including potatoes, and market gardening, which was known as truck farming because each farmer had at least one pick-up truck to take their produce to market.

For immigrants who were willing to work hard, life was good, and the American Dream was a reality. This was certainly true for William and Annie and their contemporaries. Many of them made a good living and were able to improve and maintain their prospects by the time the Great Depression began in 1929. This is further substantiated by the story of Owen Joseph Hall and his brother Theodore James who emigrated from Badsey to Ohio in 1872, but returned in 1877 with a suitcase full of gold coins according to one of his descendants.

During the Great Depression, millions of U.S. workers lost their jobs. By 1932, twelve million people in the U.S. were unemployed. Approximately one out of every four U.S. families no longer had an income. In 1930, more than 200,000 evictions took place in New York City alone, as renters could not pay their bills. Across the United States, farmers facing low prices for their products often lost their farms to foreclosure. While those of European descent faced difficulties during this period, racial minorities faced even greater hardships. For most of the depression, unemployment rates for African-American men were around sixty-six percent. Women of all races also experienced employment setbacks. In many cases, as companies began to lay off workers, they would fire women first in the belief that men needed the jobs to support their wives and children.

The Great Depression especially hurt Ohioans. By 1933, more than forty percent of factory workers and sixty-seven percent of construction workers were unemployed in Ohio. Approximately fifty percent of industrial workers in Cleveland and eighty percent in Toledo were out of work. In 1932, Ohio's unemployment rate for all residents reached 37.3 percent. Industrial workers who retained their jobs usually faced reduced hours and wages. These people had a difficult time supporting their families, and many of Ohio's city residents moved to the countryside, where they hoped to grow enough food to feed their families. William and Annie had retired by the time of the 1930 census, and were renting their home at 59 Parkman Road, Burton, Geauga, Ohio. They were still living next door to their daughter Eva Gorton and her husband George, who was described as a farm operator, and who were well enough off to have a housemaid. George died in 1932, but Eva was still running the farm with hired help in 1940, so the family seemed to have weathered the financial storm. Farmers in Ohio were also fortunate to be able to carry on during the 1930s when the weather conditions and highly mechanised farming led to the Dust Bowl wiping out the livelihoods of many settlers in the panhandle states of Texas and Oklahoma.

In conclusion

In conclusion, the families who left Badsey and Aldington for America in the 1870s and 1880s to escape unfavourable economic conditions at home made a success of their lives and ended their days in comfortable economic circumstances. Their knowledge of agriculture and market gardening gave them a skill set that gave them a chance to prosper in a developing economy, and their hard work brought them success. Their descendants also worked hard and became successful in their own right, although none of William and Annie’s grandchildren were farmers.

Shirley Tutton, January 2021