Hubert Gaukroger moved to Badsey in about 1908. Second Lieutenant Gaukroger’s name is recorded on the war memorials in St James’ Church, Badsey, and St Leonard’s Church, Bretforton.

Hubert Gaukroger moved to Badsey in about 1908. Second Lieutenant Gaukroger’s name is recorded on the war memorials in St James’ Church, Badsey, and St Leonard’s Church, Bretforton.

* * * * *

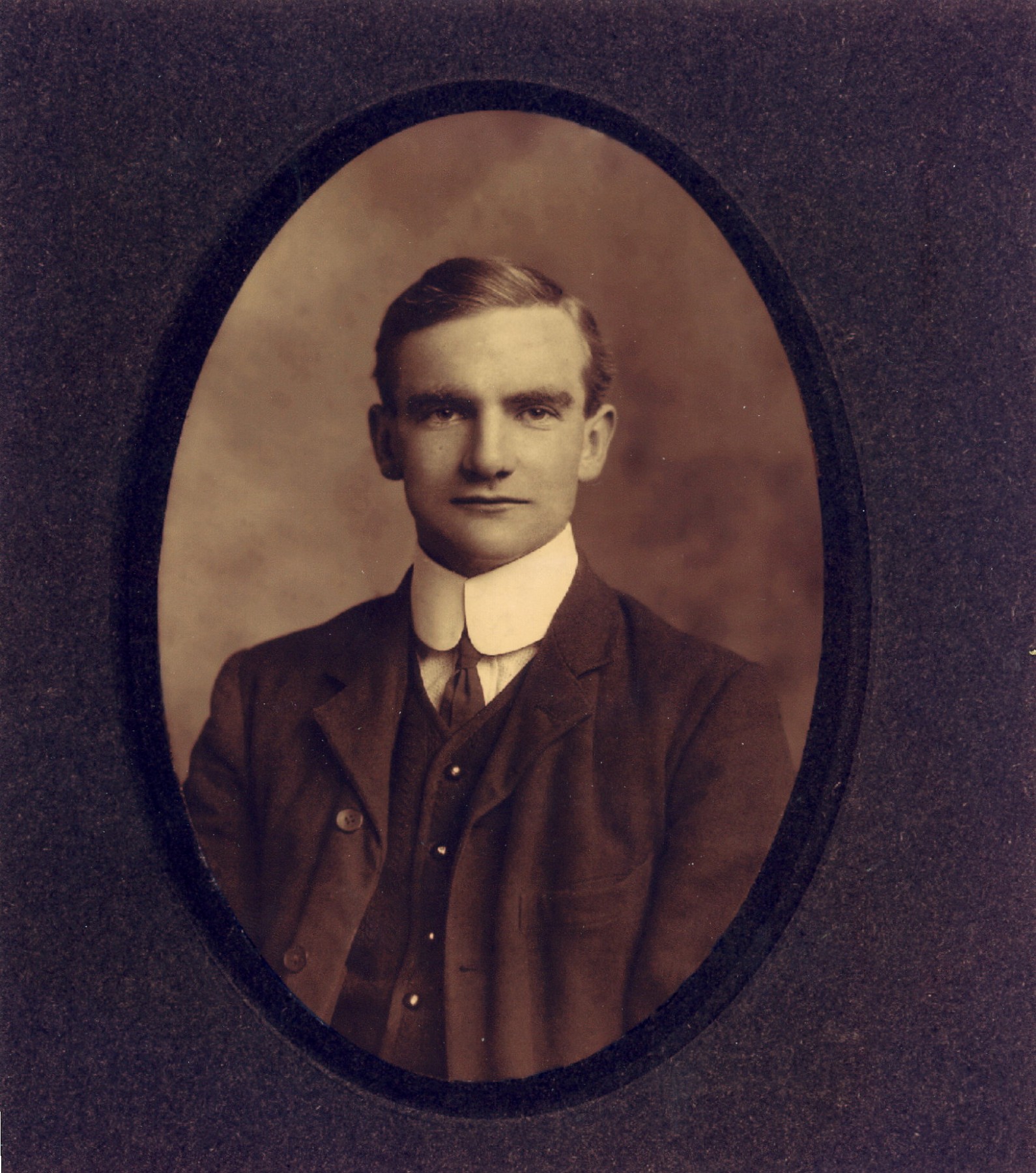

Hubert Gaukroger was born at Manchester on 10th September 1885, the youngest son of Young and Mary Hanson Gaukroger. He had six older brothers and one older sister: Charles (1872-1942), Harold (1873-1952), Vincent (1876-1961), Edwin (1878-1959), Alfred (1880-1952), Wilfred (1883-1883) and Marion (1884). By the time that Marion was born, the Gaukrogers lived at The Beeches, West Didsbury, Didsbury, Manchester. Hubert was just two years old when his mother died in May 1888.

In 1891, young Hubert was living at The Beeches with his widowed father, six older siblings, his great-aunt Elizabeth and three servants. By 1901, Hubert was living with four siblings still at home at The Beeches with their father and three servants.

In 1906, Hubert moved to the Vale of Evesham to take up market gardening. He was living in Badsey by April 1908 as his name is recorded in the Parish Magazine as having suggested at the Easter Vestry the formation of a group to tidy the churchyard. He was a keen cricketer and, for a time, was a regular member of the Evesham team, and sometimes played for neighbouring villages.

%20c1911.jpg) On 21st February 1911, Hubert married Eva Mary Byrd in St James’ Church, Badsey. Eva was five and a half years his senior and came from an old Badsey family which had owned many acres of land in Badsey and Aldington at the time of Enclosure a hundred years earlier. Over the decades, the family fortunes had become diminished and most of the remaining land was sold off by her brother in 1912.

On 21st February 1911, Hubert married Eva Mary Byrd in St James’ Church, Badsey. Eva was five and a half years his senior and came from an old Badsey family which had owned many acres of land in Badsey and Aldington at the time of Enclosure a hundred years earlier. Over the decades, the family fortunes had become diminished and most of the remaining land was sold off by her brother in 1912.

%20%26%20Eva%20-%20The%20Cottage%2C%20Bretforton%2C%20where%20%20lived%20on%20marriage%20in%201911.jpg)

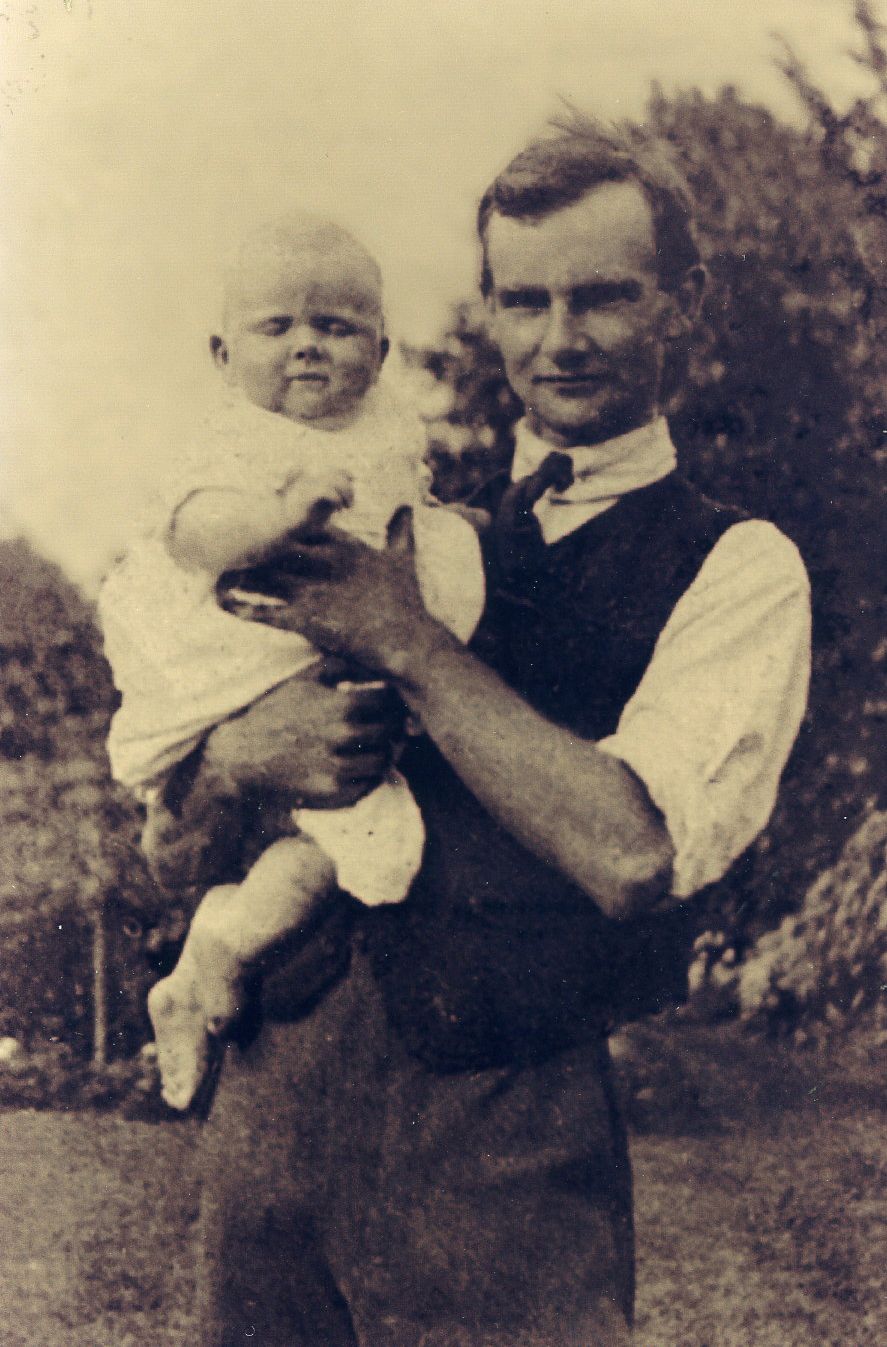

Hubert and Eva moved to a cottage at Bretforton where they were living at the time of the 1911 census. Their first-born son, James (right), was born at Bretforton on 15th December 1911. Another son followed, Robert, born on 4th September 1914, a month after the outbreak of war.

Hubert and Eva moved to a cottage at Bretforton where they were living at the time of the 1911 census. Their first-born son, James (right), was born at Bretforton on 15th December 1911. Another son followed, Robert, born on 4th September 1914, a month after the outbreak of war.

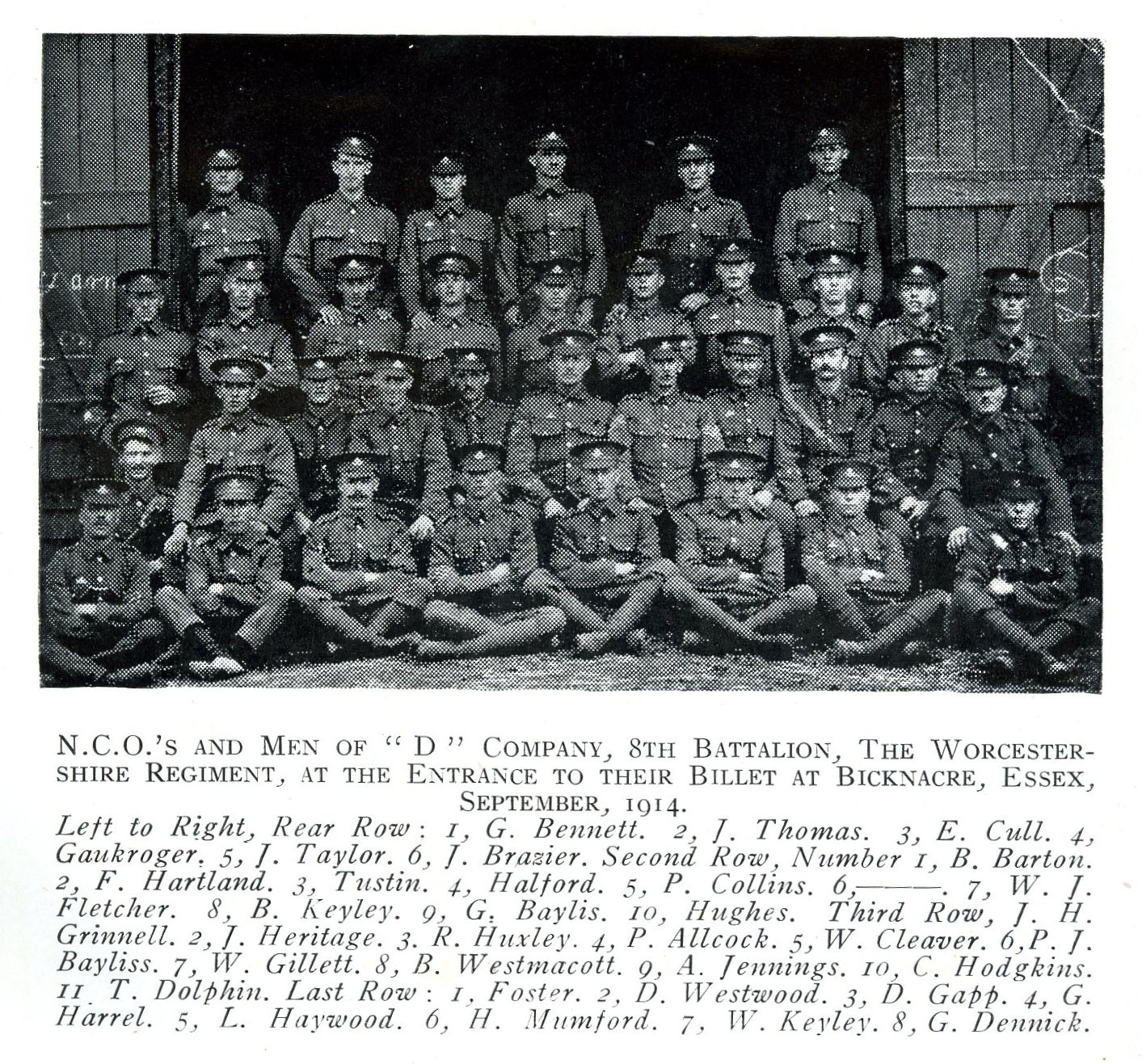

Hubert was a member of the Territorials and enlisted as a Lance Corporal with the Worcestershire Regiment in August 1914. They moved to Swindon, then to Maldon in Essex in the second week of August to concentrate with the Division and commence training, though they were in Worcestershire in November, as May Sladden, in a letter to her sister of 15th November 1914, said: “We have been up to Evesham to see the Territorials off”, and mentioned Mr Gaukroger as being one of the men they could see quite well. The Sladdens knew Hubert’s wife, Eva, very well, as she had lived for a number of years before her marriage just across the road from the Sladdens.

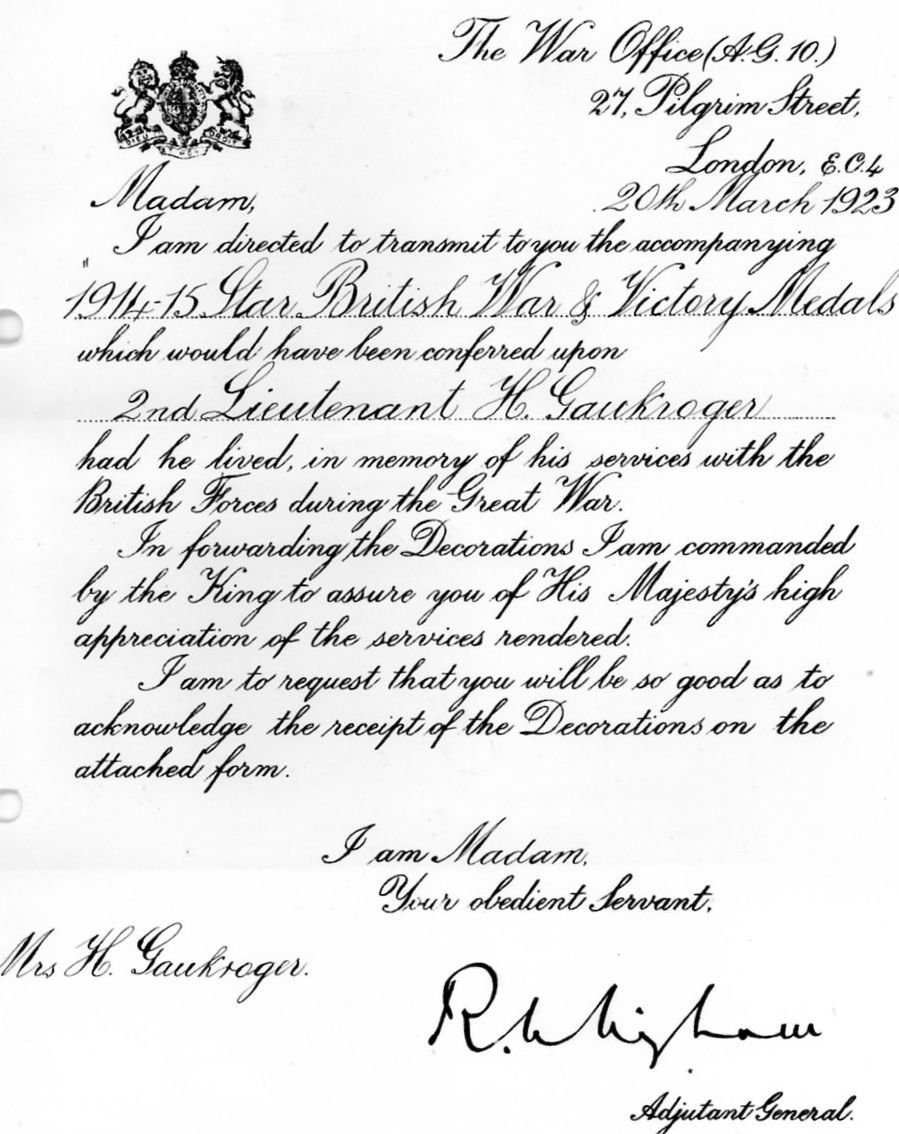

The Worcesters proceeded to France from Folkestone, arriving 1st April 1915. Two and a half weeks later, Hubert’s father, Young Gaukroger, died at his home in Didsbury, aged 87, leaving nearly £80,000. Hubert returned to England and was then offered and accepted a commission in the 1st Manchester Regiment in November 1915.

Hubert left Marseilles with the 1st Battalion bound for Mesopotamia on 8th December 1915 and arrived in Basra on 8th January 1916. The May 1916 issue of Badsey Parish Magazine reported that he had been wounded and that the wounds, which were at first thought to be slight, were now severe. Several letters written by the Sladdens in March 1916 mention his wound: Ethel Sladden’s letter of 17th March, Julius Sladden’s letter of 20th March, Eugénie Sladden’s letter of 23rd March and Jack Sladden’s letter of 24th March. The letters seem to indicate that the wound was not too serious but Hubert was out of action for nearly a year, and it was not until March 1917 that he returned to the front line in France, this time with the 2nd Battalion.

At the time that Hubert went overseas again, the Manchesters were involved in operations on the Ancre, a river in Picardy, and the pursuit of the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line. By March 1917, the Germans were in retreat, with villages destroyed, trees felled across highways and huge craters blown at every crossroads. The generals feared it might be a trap, but the Allies advanced amid rising hopes. The Manchesters laboured at Voyennes for some days, digging trenches, putting up wire and filling craters. By 25th March they were on the east bank, holding the bridgehead at Buny. The enemy retreat was certain. The previous autumn, the Germans had begun constructing a new defence line, which the British called the new “Hindenburg line”. It was not a connected line of trenches but a complex system four or five miles deep, strengthened with enormous belts of barbed wire, deep tunnels and hidden concrete pillboxes.

Operations against the Hindenburg Line outposts began on 1st April when Savy Wood and village was taken. A little railway ran through the wood, partly on an embankment and partly in a cutting. Early next day, under incessant shellfire they advanced to the embankment, from there launching a rapid charge northwards, parallel to the main German front. The enemy had destroyed most of the woods and all the buildings, leaving almost no cover. Francilly-Selency was attacked on 2nd April in what was judged to be one of the battalion’s greatest exploits. But it was in this attack that Second Lieutenant Gaukroger lost his life; he was killed on the railway bank as the attack started.

A fellow officer in the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment was the poet, Wilfred Owen. At the time, Wilfred Owen was Platoon Commander of B Company and Hubert Gaukroger was Second Lieutenant, but Owen actually missed the events of 2nd April as he had been at a Casualty Clearing Station and did not return to the front line until 3rd April. Gaukroger’s death had a tremendous effect on Owen. In a letter to his mother on 15th April 1917, Wilfred Owen wrote:

For twelve days I did not wash my face, nor take off my boots, nor sleep a deep sleep. For twelve days we lay in holes, where at any moment a shell might put us out. I think the worst incident was one wet night when we lay up against a railway embankment. A big shell lit on the top of the bank, just 2 yards from my head. Before I awoke, I was blown in the air right away from the bank! I passed most of the following days in a railway Cutting, in a hole just big enough to lie in, and covered with corrugated iron. My brother officer of B Coy [Company], 2/Lt Gaukroger lay opposite in a similar hole. But he was covered with earth, and no relief will ever relieve him, nor will his Rest be a 9-days’ Rest. I think that the terribly long time we stayed unrelieved was unavoidable; yet it makes us feel bitterly towards those in England who might relieve us, and will not.

This was the incident that got Wilfred Owen officially diagnosed with shell-shock. The Manchesters left the line in the early hours of 22nd April. Wilfred struggled to behave normally, trying to forget that he was still dizzy from the shell-blast and sick with the memory of Gaukroger’s scattered remains. He was admitted as a patient at the Casualty Clearing Station at Gailly, which was now a specialist hospital for shell-shock cases. There, under the care of senior neurologist, William Brown, an eminent man in his field, he learned to talk about his experiences. The essential first stage in recovery was to identify the moment of failure, the breaking point that each man most wanted to hide. Only a week after arriving at the Casualty Clearing Station, Owen was able to write to his sister, Mary, on 8th May 1917, saying that the cause of his collapse had not been the blast on the railway bank but sheltering near Gaukroger’s remains, an insight he must have reached with Brown’s help:

You must not entertain the least concern about me because I am here. I certainly was shaky when I first arrived. But today Dr Browne was hammering at my knees without any response whatever. (At first I used to execute the High Kick whenever he touched them) i.e. Reflex Actions quite normal. You know it was not the Bosche that worked me up, nor the explosives, but it was living so long by poor old Cock Robin (as we used to call 2/Lt Gaukroger), who lay not only near by, but in various places around and about, if you understand. I hope you don't!

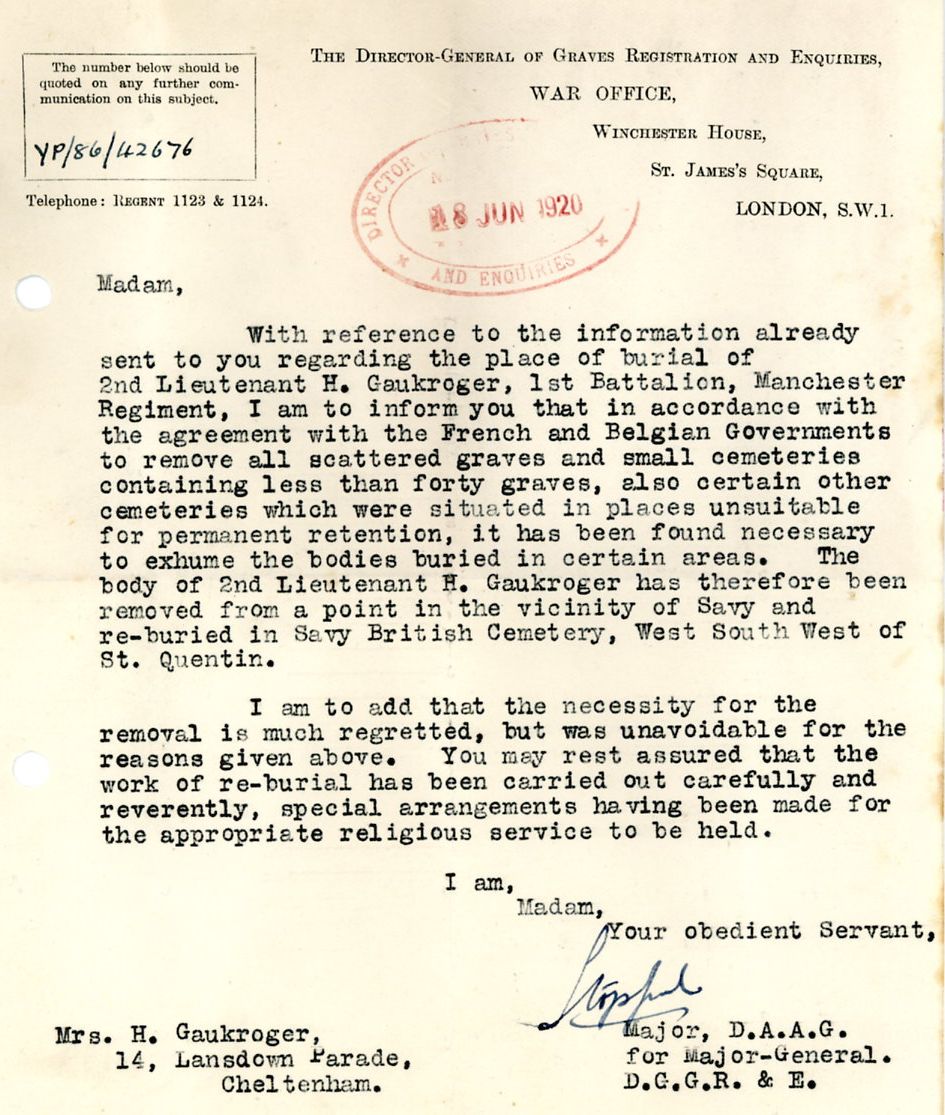

Hubert Gaukroger had presumably been buried in the cutting and later horribly disinterred by a shell. Hubert was initially buried at Roupy, the next village south of Savy, but his body was later removed to Savy British Cemetery which was made in 1919. Details of headstone schedules on the Commonwealth War Graves website reveal that Hubert’s widow, Eva, requested that the words “Thy will be done” should be added to the headstone.

The Badsey Parish Magazine of May 1917 reported his death as follows:

Our readers will have heard with regret of the death of Lieut H Gaukroger. Lieut Gaukroger volunteered early in the war and had seen active service both in France and Mesopotamia, being wounded on the latter front over a year ago. He went out again to France in March, before he had thoroughly recovered from the effects of his wound, and was reported as missing on April 2 and afterwards as killed-in-action on that date.

As he had lived in both Badsey and Bretforton, he was named on both war memorials.

At the time of Hubert’s death, Eva Gaukroger and her sons were living at Teignmouth, Devon, where Hubert had bought them a house when he went out east. Eva never remarried. For a time immediately after the war, she lived at 14 Lansdown Parade, Cheltenham, and then went to live at Witney. She died at Oxford in 1971. Hubert’s sons, James and Robert, died in 2001 and 2002 respectively.

* * * * *

We are grateful to the late Rosy Freudenberg (granddaughter of Hubert Gaukroger) for allowing us to publish copies of family photos and documents.